The Funk Factor: Brettanomyces, Lactobacillus, and Pediococcus.

I ruined a blonde ale once by not washing my hands after handling a sour fermenter. Three weeks later, the beer smelled like feet and Band-Aids.

While bacteria often means spoilage in a kitchen, it can be the main character in fermentation. Understanding the differences between these microbes is essential for brewing funky farmhouse ales or lambics.

Once introduced to your lab, these wild microbes are never fully gone, often hiding in the threads of plastic equipment. This guide explains how each one behaves and how to manage them safely in your brewery.

Lactobacillus: The Clean Sourer

Lactobacillus is the workhorse of fast souring, the same bacteria that turns milk into yogurt. In beer, it drops the pH quickly by producing lactic acid, resulting in a clean sourness similar to lemon juice.

I use Lactobacillus for kettle sours because it works rapidly under anaerobic conditions. Within 24 to 48 hours, the pH can drop from 5.2 to between 3.2 and 3.8 before you boil the wort to kill the bacteria.

This method is safe because the bacteria cannot survive the boil, allowing you to sour without ongoing risks in the fermenter. The primary challenge is its hop sensitivity; even small amounts of alpha acids can stall the process entirely.

Lactobacillus species are facultative anaerobes that convert simple sugars into lactic acid. Because they lack the enzymes to tolerate high concentrations of iso-alpha acids, they are generally restricted to worts with less than 5-10 IBUs.

To speed up souring, add a handful of unmilled grain to the wort. The grain husks carry natural Lactobacillus cultures that give the fermentation a significant head start.

Pediococcus: The Slow Sourer

Pediococcus is essential for complex styles like lambics and Flanders red ales, but it is slow and unpredictable. Its most infamous trait is the production of “slime,” making the beer look thick and ropy during the early stages.

This ropiness is temporary, as Brettanomyces eventually consumes the slime over several months. What remains is a complex sour beer with deep layers of acidity and fruit that Lactobacillus cannot replicate.

The main downside is the production of buttery diacetyl, which tastes like butterscotch. Because Brettanomyces is required to clean up both the slime and the diacetyl, these two microbes are almost always used as a team.

The “ropiness” caused by Pediococcus is due to the secretion of exopolysaccharides (EPS). Brettanomyces produces extracellular enzymes that break down these complex carbohydrate chains, effectively thinning the beer back to a normal consistency.

If you use Pediococcus, plan for at least six months of aging. Do not bottle early, as the slime and buttery diacetyl need significant time to fully break down.

Brettanomyces: The Wild Yeast

Brettanomyces (Brett) is technically a yeast, not bacteria, but it behaves differently than standard brewer’s yeast. It consumes complex sugars and dextrins that regular yeast cannot touch, resulting in a bone-dry finish.

Its flavor profile ranges from tropical fruit like mango to “horse blanket” funk. Brett works slowly and is often used in secondary fermentation to add character and reach a very low terminal gravity, sometimes below 1.002.

Cross-Contamination Risks

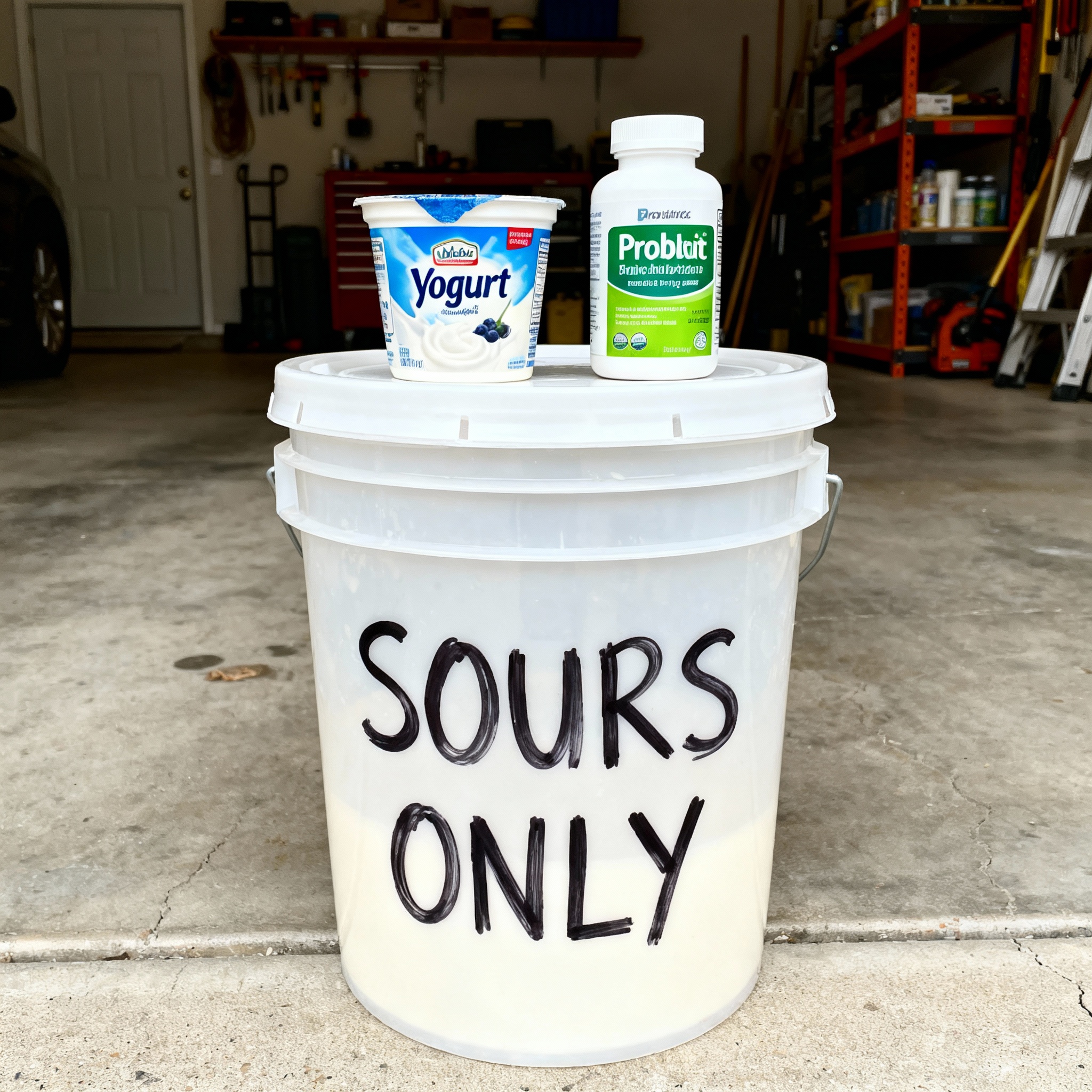

Once you brew sours, you absolutely need separate plastic equipment. These microbes hide in microscopic scratches and porous surfaces that sanitizers cannot fully penetrate.

- Plastic Gear: Dedicate specific buckets, tubing, and bottling wands for “Sour Gear Only”.

- Non-Porous Surfaces: Glass and stainless steel are safer as they can be effectively sterilized with heat or strong chemicals.

- Airlocks and Gaskets: These are inexpensive to replace, so keep a separate stash marked specifically for sours.

- Personal Hygiene: Microbes are sticky and can transfer via your hands or even a shirt sleeve if you handle clean beer on the same day.

Label your gear with a permanent marker. It is far cheaper to spend 40 batch of clean beer to a wild infection.

Co-Pitching Strategies

The easiest entry into wild brewing is using a pre-mixed culture like Wyeast 3763 (Roeselare Blend). In these blends, Saccharomyces ferments first, followed by the bacteria dropping the pH, and finally, Brett polishing the flavor.

For more control, you can use “staged fermentation” by pitching clean yeast first and adding wild bugs later. This allows you to manage the timeline and determine exactly how much funk or acidity you want in the final glass.

| Microbe | Souring Speed | Primary Flavors | Special Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lactobacillus | Fast (24-48h) | Clean lemon, Yogurt | Extremely hop sensitive |

| Pediococcus | Slow (Months) | Sharp acid, Complex | Produces temporary slime |

| Brettanomyces | Very Slow | Barnyard, Fruit, Leather | High cross-contamination risk |

Conclusion

Making a great sour beer is a lesson in patience and respect for microbiology. Lactobacillus provides the quick tang, Pediococcus offers the deep complex acid, and Brettanomyces ties it all together with its unique funk.

Separate your gear, take your time, and don’t be afraid of the slime. With the right microbes and enough time, you can transform a simple wort into an elegant, world-class wild ale.

References

- Milk The Funk. “The Wiki.” milkthefunk.com.

- Tonsmeire, M. “The Mad Fermentationist.” themadfermentationist.com.